Forget whether it was brig or brigantine. The archaeologists who are trying to decipher the 18th-century ship recovered this summer from an old landfill at the World Trade Center site had to agree first on whether they were looking at its bow or its stern.

Only about half the vessel — 32 feet — survived the construction of a retaining wall roughly along the line of Washington Street, close to what was once the edge of the Hudson River. To unseasoned eyes, the fanlike array of ribs at one end of the mud-encased craft strongly suggested that it was the stern.

But more discerning experts like Warren Riess, of the Darling Marine Center at the University of Maine, recognized in the same pattern the lowermost portion of a bow.

It wasn’t until the wooden elements of the hull were gingerly removed by AKRF, a consulting firm, from the archaeology excavation site in Lower Manhattan, cleaned up at the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory and inspected by shipwrights from Mystic Seaport in Connecticut and other nautical archaeologists that the question was settled.

A gudgeon helped seal the case.

Archaeologists had noted the presence of at least one metal ring, either wrought iron or steel, at whatever end of the vessel they had come upon.

Close inspection in the laboratory disclosed that the shape, in cross section, was what one would expect to see in a gudgeon. These are metal rings, fastened to a stern or rudder post, into which pins known as pintles are inserted. Pintles support the rudder and allow it to move back and forth. Gudgeons and pintles together, in other words, form a hinge.

(Thirty-six years in this business, and never before have I had the chance to use the words gudgeon and pintle in an article.)

AKRF This gudgeon told archaeologists they were looking at the ship’s stern.

There was another important clue. As the structural members of the hull were cleaned, Dr. Riess said, investigators got a much better look at the endmost vertical timber. It was relatively straight, as one would expect in a stern post, rather than curved, which would have indicated the bow.

And there’s the rather uncanny fact that most of the 50 or so wrecked and derelict vessels that have been excavated in recent years have been found listing to port. Carrie Atkins Fulton, a Cornell graduate student, pointed this out to the team working on the World Trade Center project.

“It turned out she was right,” Dr. Riess said. “It does list to port.” (If the visible end of the boat had been the bow, it would have been listing starboard.)

Until last week, no trace of the masts had been discovered where one would expect: on the keelson, the lengthwise beam inside the ship that was fastened to the keel below.

But on a visit to the conservation lab on Aug. 31, Dr. Riess said he found what might be an indication of a mast step — a framework into which the heel of a mast was inserted — at one end of the portion of the keelson that was recovered. “That would put it about in the middle of the ship,” he said, “a reasonable place for it to be if this were a two-masted ship.”

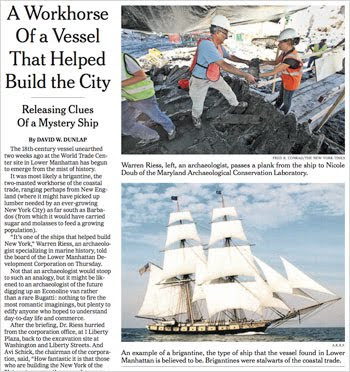

The overall dimensions of the vessel allowed Dr. Riess, with some confidence, to tell the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation on July 29 that the vessel was most likely a brigantine, the two-masted workhorse of the coastal trade.

Unfortunately, in the slide show he presented, prepared by AKRF, a brig was shown — not a brigantine. Technically, both of a brig’s masts are square-rigged (square-shaped sails hanging from yards), while only the foremast of a brigantine is square-rigged. Even more unfortunately, the vessel was far from a generic merchant ship.

More unfortunately still, The New York Times picked up the illustration for use in the newspaper. And Times readers, who are expected to know such things, took us to task. Here’s what John Baker of Erie, N.Y., had to say:

You really blew it!! The photo at the bottom of the article was a brig, not a brigantine, and was a warship, not a merchant vessel. It is the U.S. Brig Niagara that captured the British squadron in 1813. Not many lumber ships carried 24 cannon! I assume you are a young intern who will check his facts better in the future.

Mr. Baker was much kinder in a later e-mail and explained that his ire arose in part because he had spent five years as a volunteer on the Niagara.

It turns out that the archaeologists who prepared the slide show for the development corporation board were — to put it mildly — multitasking at the time. “We put that together overnight from our hotel rooms, on our BlackBerrys, and through a series of frantic phone calls to the office while working 14-hour days removing the ship remnant itself,” Michael Pappalardo explained. “The image was intended to be a stand-in for what our remains may have looked like, and not to stand up to the scrutiny of a court of law (or sharp-eyed New York Times readers).”

Dr. Riess took the kerfuffle in stride. “For a three-seconds showing to represent ‘a two-masted ship from the late 18th century, such as a schooner, brig, brigantine or snow,’ it was fine,” he said. “It was of minor importance to get that correct when so much was of higher priority.”

Besides, he added: “The terms brig and brigantine are a bit squirrelly. While today most people who care strictly distinguish the two, many people like myself, whose research is mostly in the 18th century, rarely make the distinction. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, most people did not make the distinction, or disagreed about it.”

That suggests that no one will ever be able to say for certain whether the S.S. World Trade Center was brig or brigantine, schooner or snow. But at least they now know which end was up.

Source from great site : http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com

No comments:

Post a Comment